Revolutionize Methods at Wilson Foundry Plant

$1,500,000 Spent for New

Equipment and Buildings to Increase Production of Overland and Willys-Knight

Motors

By D.R. Wilson

Vice-Pres. and Gen. Mgr., The Wilson Foundry and Machine Co. Pontiac, Mich.

Revolutionize Methods at Wilson Foundry Plant

$1,500,000 Spent for New

Equipment and Buildings to Increase Production of Overland and Willys-Knight

Motors

By D.R. Wilson

Vice-Pres. and Gen. Mgr., The Wilson Foundry and Machine Co. Pontiac, Mich.

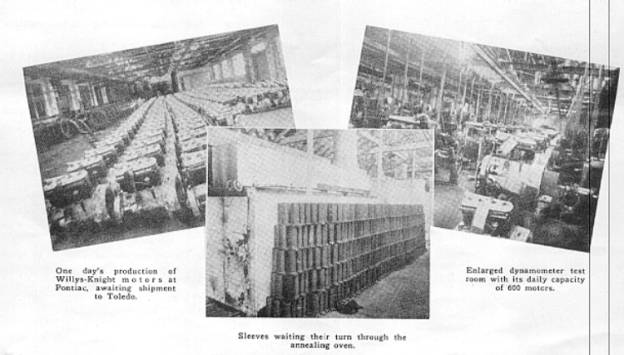

Dealers and Salesmen who visit the Toledo factory of the Willys-Overland Company should not count their tour complete without an additional trip to the city of Pontiac, Mich., about 80 miles away, which is the home of The Wilson Foundry & Machine Company, largest producers of automobile castings in the world, whose entire capacity is now devoted exclusively to the manufacture of cylinder blocks for Overland motors, Willys-Knight motors in their entirety, and the steel molds for Fisk tires.

The Wilson plant covers 35 acres and has floor space of more than one million square feet. During 1923 our gross sales aggregated $13,850,00, devoted entirely to grey iron castings, machines castings, Willys-Knight motors, and tire mold castings.

Spend $1,500,000 on Improvements

During the past six months we have spent $1,500,000 for new buildings and special equipment to meet the added requirements of the Willys-Overland organization, stepping up our capacity to meet any demand up to 1200 Overland blocks and 500 Knight motors per day.

This has been accomplished through new arrangements of present equipment, completely revolutionizing our methods of operation, as well as by the construction of new machinery which has made possible almost double our previous output without increasing our floor space.

In our aluminum and grey iron foundries, new methods of operation now permit us to take our molds to the metal, instead of the metal to the molds. Continuous pouring, with conveyors, has enabled us not only to achieve economies in space and time, but also has minimized waste of material, which has always been the chief bugaboo of the iron foundries.

Start With Laboratory

To give a brief outline – for it must of necessity be brief in order to limit myself to the space allotted – of a few of the more important operations which we perform for Willys-Overland, I must start at the beginning, or the laboratory. Here, you might say, is the very heart of our organization. Not only does this department furnish us with the specifications for the purchase of our raw material, but it analyzes and inspects it and then keeps a daily check on the ingredients that we receive. In order to take advantage of the raw material available it is frequently necessary to juggle certain elements to maintain the desired carbon, Brinnell test or some physical requirement, and whenever a given element is thus juggled, it is generally necessary to juggle certain other elements in the opposite direction to gain the required balance. All analyses are made from samples obtained by drilling test bars. On all standard mixes that come from our furnaces, a test bar is cast every hour and on special mixes every twenty minutes.

Further instances of the activity of out metallurgists will be recounted as we progress in out verbal picture of out plant’s activities.

1200 Carloads of Sand

Castings cannot be made without molds and a necessary part of our molds are the cores. To many visitors our core-making is probably the most interesting of the many phases of our work. Cores are made of sand, linseed and some water, around which the molten metal is poured for the metal castings. For these cores we have a large building, 80 feet wide and 390 feet long, in which is stored the lake sand that we use. This building will hold 1200 car loads. Two grades of sand are used for the core sand and the other for molding purposes.

The sand for the cores is mixed in two large steel hoppers. These hoppers are surmounted by a double hopper bin, each of which contains one grade on sand. Under each bin is a measuring gate that contains a certain cubic content of sand. An air cylinder serves to operate this gate and deliver into the mixer a measured amount of sand.

The necessary oil and water are

forced in under compressed air. Careful

experiments have been made to determine the proper mixing time for each batch

and the machine operator has a clock which enables him to determine the time

before the discharge gate is opened.

The sand coming from the discharge gate of the mixer falls directly into

the carts and is taken to the core room.

Inspect Sand Piles Daily

All sand heaps are inspected daily

by our laboratory force and a mixture and porosity test is made. The moisture determination is made by

treating a weighed quantity of sand for evaporation of moisture between the

temperatures of 100 and 101 degrees Centigrade. The porosity test is made by an instrument known as the

“Castrite” which splits a flow of compressed air between two orifices. Any resistance that is felt at one of these

openings will naturally increase the flow through the other, which is promptly

recorded on the gauge.

To describe in detail the

activities of our core room would fill a ponderous volume. Cores are made of various parts that we

manufacture by men and girls, each working at individual benches. Opposite each is a set-off bench on which

the operator sets the cores on completion and when the plate is filled it is

placed on the rack. These racks, when

filled are then placed in one of the battery of seventy coke ovens, heated by

fire boxes under the floor level. The

heat enters the oven at the floor level at the back, ascends and circulates

about the cores and the moist air is forced into the pocket below the floor level. Doors are heavily insulated and the ovens

dry with a minimum amount of coke per ton of core sand dried.

Make Cores Ready for Foundry

All core ovens are under accurate temperature control, the oven being equipped with recording pyrometers. The firing of the ovens is so conducted as the furnish the desired amount of heat, and regulation of each oven is accomplished by means of dampers.

We now come to the core assembly. Here cores are ground down and fitted to exact sizes and then when necessary are pasted into definite assemblies. These units are mounted on assembly conveyors and pass around on the carriers before a series of operators who are commissioned to perform by one task. One looks after gauging of particular spots, another cleans out vent, still another puts in stopping for holes, and so on. Where surfaces of exceptional smoothness are required the cores are sprayed with a blacking and are then put on racks before delivery to the foundry on the following day.

All of the cores are delivered to

the foundry ready for use and no molder is allowed to do any filing or rubbing

of a core. If by chance any core does

not fit, it must be returned to the core room, but with our system of jigging

and testing core assemblies it is rarely that a misfitted core reaches the

foundry. Having core or care assembly

accurately fitted reduced the labor of core setting in the foundry to a

minimum, and increases the molder’s output.

Laboratory Watches Melting

All this time the grey iron for these cores has been in the preparation on our cupolas. Recent additions to the extent of a quarter of a million dollars in our case iron foundry include additional cupolas, or furnaces, where the pig iron and coke are converted into grey iron. We can melt 470 tons daily if this output is found necessary.

The melting of the iron is under

the direction of a representative of the laboratory, who personally supervised

the charge that is delivered into each cupola.

At one time our cupolas were equipped with regular charging machines,

but we found that these were not accurate enough, so after a series of

experiments costing thousands of dollars, we decided to abandon all mechanical

methods in favor of hand charging. Now

the weighted charge of coke is placed before each cupola. To this is added a weighed charge of limestone

and then the metal is brought up and carefully distributed. Each of our larger cupolas has a capacity of

seventeen tons per hours.

Melt 73,223 Tons in 1923

In front of each cupola is a

three-ton receiving ladle with a skimming spout, and this pours directly into a

1000-pound bull ladle, suspended on a monorail. Connected to this is a dial, which tells the operator the weight

of the charge in the receiving ladle, so that he can put a predetermined amount

of metal in each bull ladle. A very

careful study has been made of the number of pounds of metal required to a

given number of castings of a certain kind, and each ladle is filled to take

care of the castings it is to pour. A

designating number is hung on each ladle, telling not only the composition of

the metal it contains, but also its destination.

During 1923 our iron foundry melted

73,223 tons at a temperature of 2600 degrees Fahrenheit. One pound of coke will melt six pounds of

iron.

We are now at the point where the

metal is ready for the mold. The cores

are taken to the foundry. They are

securely placed in jogs and now comes the revolutionizing method in our

operations. Instead of bringing the

metal to the molds, we take the molds to the metal by means of conveyors.

Pours 300 Cylinders in 9 Hours

On Page 2 you will see a picture of

a Beardsley-Piper Sand Slinging machine.

Last year we operated this machine on a track. It would be set at the farthest point of its track. Molding sand would be placed before it and

it would go rooting its way through this sand to fill the molds. After the molds were ready they were then

filled with metal which was brought to the molds. Now all this is changed.

This huge mechanism is now stationary.

Sand is brought overhead by a vast system of tubes from mixing

machines. It is firmly packed around

the molds and is then placed on conveyors.

At a given point, nearest to the cupolas, this mold then meets the bull

ladle and the metal is poured. It is

then allowed to cool, the casting is dumped; sand is dumped from the mold, is

automatically carried back to the mixer, where it is sieved and cleaned – and

the entire operation is once more repeated.

The Beardsley-Piper Sand Slinging machine, which molds Overland cylinders, pours 300 cylinders in nine hours, handling 350 cubic feet of sand, or 161 tons per day.

90,000 Pounds of

Aluminum Daily

The story of our new and modern aluminum foundry is similar to this. Hear we have spent half a million dollars for new equipment which operates on the identical principle just explained.

Our new battery of six furnaces makes is possible for us to melt 90,000 pounds of aluminum per day, which is ample material to build 500 sets of aluminum engine parts daily.

During 1923 we melted 9,287,640 pounds of aluminum, which is going to be increased considerably this year. Each charge is melted within 20 minutes and is poured into the castings at a temperature of 1100 degrees Fahrenheit.

In our aluminum foundry all

castings are made with green sand cores, following the general practice already

outlined for grey iron.

Proud Sleeve Production

All core and mold setting jigs used

in the foundry are under constant inspection of tool and pattern rooms. Besides, a certain number of castings are

cut up from time to time to make sure that core boxes, patterns, and jogs are

functioning properly. Other castings

from each day’s run are put through the shop in advance, so as to check up on

all operations, including coring, molding and the metallurgical work.

Necessarily, only castings made in our plant can be tested in this way, but

inasmuch as Willys-Knight motors are completely machines, it makes it possible

for us to keep an accurate check and inspection on output.

There is one feature of our

production in which we take a great deal of pride – the sleeves for

Willys-Knight motors. One of the most

difficult problems that we have had to solve has been the casting of these

parts. They must be absolutely free

from dirt and porosity, must be strong and must have exceptional wearing capabilities. These sleeves are cast with the greatest

care from first operations to the last.

Then they are rough turned after several months’ seasoning in the open

and are passed through an annealing oven, which heats the castings up to a

temperature of 800 degrees and delivers them cooled so that they can be handles

immediately after coming out of the oven, so that they can pass into the

machine line-up for finishing. The oven

works on an endless conveyor system, being loaded at one end and discharged at

the other. This low temperature anneal

has the effect of aging castings, which relieves strains and results in a more

nearly finished product.

A trip through the machine room is

a never-failing source of wonderment, particularly during the last six months

since we have installed a new battery of machines which have enabled us to

double our output without increasing out floor space. Grinders, reamers, bores in quantity to amaze, meet one’s eyes

here, but the have become necessary if we are to keep pace with the public’s

demand for Willys-Knight cars.

Our new motor assembly room,

climaxed by a big, roomy dyanometer room, where Willys-Knight motors are first

run under factory power and then tested under their own power, are two other

places in which the visitor finds much to interest him.

Pontiac Plant Bids You Welcome

But these are only high spots that

I can touch in order to condense my story of the activities of 4000 men to the

space allotted to me.

The Wilson Foundry & Machine Company wants to take this means of extending a hearty welcome to all who visit Toledo to add a day to their itinerary for the purpose of visiting our factory in Pontiac.